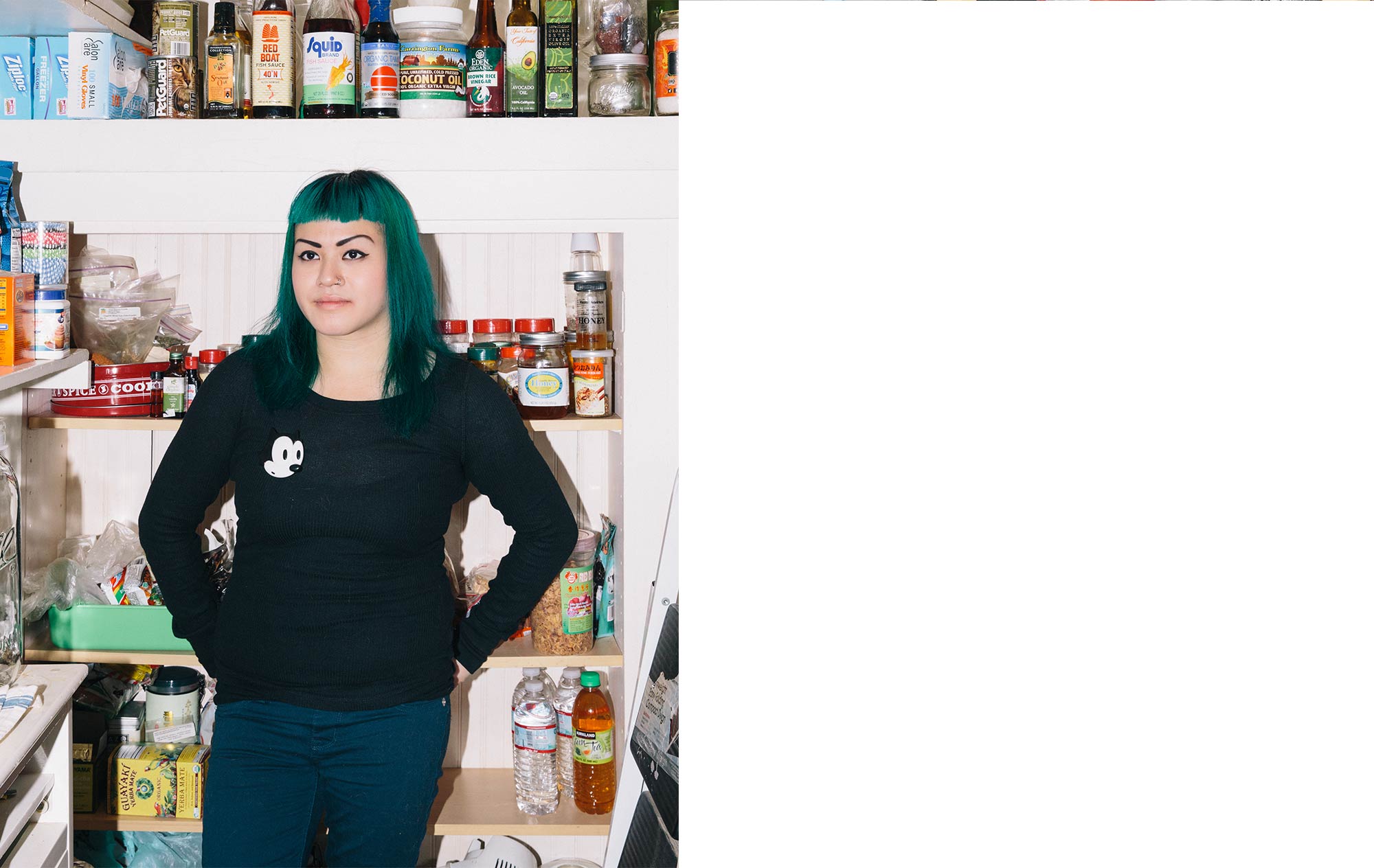

Julia Pham, 25, a self-taught chef, operates Relish Underground Dining in her apartment and works at True Nature Foods, where she sells organic juices, produce, and meat. She’s used those experiences to explore the use of local ingredients in ethnic cooking—and to build an eclectic community of food lovers.

Interview by Brianna Wellen

Photographs by Ryan Lowry

I moved around a lot as a kid. My parents got divorced when I was two. When I was eight I moved in with my dad in San Jose, California. It was pretty rough there. My dad found out that my brother had a meth addiction when I was 15 and my brother was 17, and my brother left home and left me there with my dad. Things were really strange and awkward. So I moved in with my mom for six months. Things were also rough there. She kicked me out of her house when I was 16. No one took me in except for my aunt here in Chicago, who owns [Vietnamese sandwich shop and bakery] Ba Le. I’ve been here ever since.

I don’t talk to my parents. We have a weird relationship. They just don’t get what I do. But I’m really close to my aunt; she’s like my mom. I worked for her for six years. I started out as a cashier at Ba Le, then five years into it I became a manager and her public representative. So I learned how to manage the kitchen and the front of the house, and I talked to people about our identity in the Vietnamese community. I learned a lot from that job, a lot about business and what people want when they go out to eat. I drew a lot of inspiration from my aunt because she was managing a lot of it herself. I was always trying to match that.

Before I became manager, my grandfather had passed away. I learned about my grandfather’s history and was completely blown away. He started Ba Le in Vietnam and came to America and started teaching people how to run their own businesses. There are Ba Le bakeries all across the country. That really resonated with me, and I wanted to explore food on my own.

I left Ba Le to go back to school. I was going into art education at the time, but when I was there I just felt like that was not the place for me. Because I hadn’t had a conventional life, this conventional path wasn’t working. So I left and started working in different kitchens, and along the way I just felt really unfulfilled because I had this voice inside of me saying, “Make this, make that,” and at work I was just making whatever my bosses wanted me to. I really needed an outlet. I had a dream about serving people in my apartment, and I woke up and just said, “OK, I can make that happen. Let me find a bigger space, let me find dishes and a table, and I can just do it myself.” And that’s what I did. I moved into this apartment, and I started Relish.

I never felt a need to go to [culinary] school, because when I was in school for art I didn’t feel a strong need to make art. School has always made me feel creatively stunted. I figured I would just make my own education by working and getting to know different business owners and chefs and farmers. With Ba Le, a lot of being there really helped me think deeper about my heritage and the culture that lies within food and how I can translate that through my own cooking. Where I work now, True Nature, is a great place for someone like me because I get fresh local produce all the time, so I’m working with some of the best midwestern produce, and it’s going straight to my diners.

I started shopping at the Andersonville Farmers Market and talking to the farmers there and it got this stew started in my brain to experiment with different ingredients. Every week I got something different that I was unfamiliar with, and I made a dish out of it, and I came back to the farmer and talked to them about it. It was a true educational experience for me. The ingredients were really my instructors.

A lot of people come to the dinners because they hear about it from friends. It’s great because the conversation just keeps going, and there are characters at the table that I get to know and everyone else gets to know. It’s a good communal experience where people who would sit next to each other but wouldn’t normally talk to each other finally get together and share their different backgrounds. I’ve met some crazy-talented people here. I would never approach them at a bar or a restaurant or anything like that, so it’s really cool that I can connect with them. I’m learning more and more through these people because I see that they have odd jobs too or they have a certain specialty. It really helps me see that they appreciate my food.

A lot of people have never been to an underground restaurant so a lot of them don’t know what to expect when they walk through the door. They’re really surprised that it’s cozy and that it’s an actual apartment and not a commercial kitchen. I think people like that. I think when they sit down and they have a glass of wine, they feel at home so they talk a little bit more instead of feeling intimidated.

I think that at higher-volume restaurants it’s difficult to meet the demands of so many people. For me it’s putting out a menu with love and providing just that. It’s sustainable for me, for the earth, and everyone that comes here. Instead of serving 30 people, I would rather serve 15 people if I know that it’s not too much on any of us. It’s affordable for them, it’s doable for me, and it’s not harmful to the environment.

I took the summer off to do some soul-searching, and I followed Eddie Huang of Baohaus in New York. He talks about authenticity, especially in ethnic cuisine. I wanted to present something that’s straightforward and something that I can really focus on and master. I think that simplifying the menu with two courses instead of four really gives me a chance to say a lot more. I don’t have to fill in gaps; it’s just two things that I love and see the connection in, and other people can see that too.

One of my favorite dishes I’ve cooked is khao soi, which is an egg noodle Thai dish. That was my favorite because it was the spiciest, and I really wanted to focus on southeast Asian flavors. I dared to go there. Before I was worried—what if people can’t handle peppers? But with that dinner I wasn’t compromising.

Being Vietnamese, being kind of an outcast in many social circles and the culinary scene, I think it’s important for me to tell my story. That’s why I do this. ●